Sundials through the Ages

Ancient

Medioeval

Medioeval

Humans have long tracked time through the day, the seasons and the years. Original designs were important to track the seasons for agriculture.

Medioeval

Medioeval

Medioeval

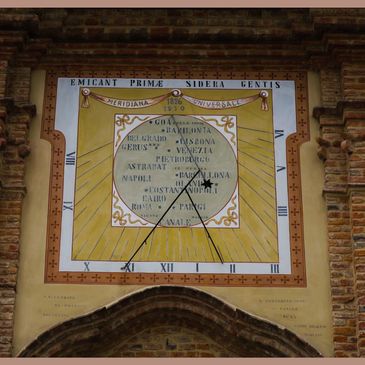

European dials became widespread on churches, marketplaces and public buildings. They generally mark the hours of the day, and particularly the Noon line.

Modern

Medioeval

Modern

New dials are still being designed and constructed in very novel shapes.

How they work

The first thing to understand about a sundial is that even the best of them are only accurate to clock time four days each year. That’s not a defect, just an artifact from Earths elliptical orbit around the Sun. A clock tracks the average 24 hour length of a day. A sundial directly reads the position of the Sun in the sky. The two can be off by 16 minutes in the Fall and Winter and 6 minutes during the Spring and Summer.

There is a fix for that - a way to read a sundial very close to clock time. A good sundial will have an analemma, a figure-8 shaped curve which shows the correction factor for each day. By reading the dial directly, then adding or subtracting the correction factor you can get remarkably accurate time. The analemma is created by making a mark each day at precisely the same clock time, usually Solar noon. That’s a lot of work for most, but even once per week will plot out an accurate curve.

The next important thing to understand is that the larger a dial is, the more precise it can be. A small, horizontal garden dial looks nice but is difficult to read to within a few minutes of clock time. A vertical dial does not take up much real estate and can be as large as the wall it occupies. Additionally, a vertical dial can be a calendar as well as a clock. Hours are marked by the position of the shadow, and days by its length.

The Gnomon

The Gnomon

A key part of any sundial is the gnomon, or the part that actually casts the shadow. The top edge of the gnomon needs to be parallel to the axis of the Earth so that it rotates the same relative to the Earths orientation towards the Sun. This is actually pretty easy - the angle with respect to the ground is equal to the latitude where it will be installed. It also needs to be in a true North-South alignment, so the top edge point towards the Celestial Pole (close to Polaris in the Northern hemisphere).